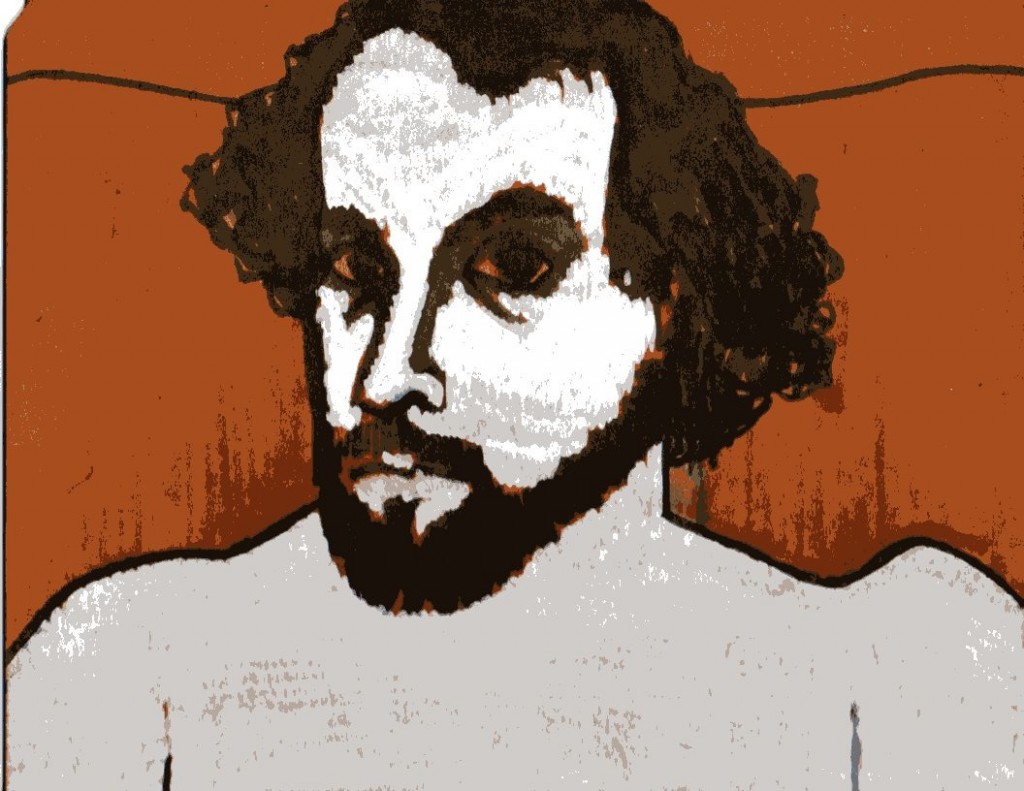

My father fled his dad’s restrictive Midwest world to move to New York’s downtown in the 1960’s, pursuing a career in art. As a bearded beatnik living on Crosby Street, Dad painted vivid, colorful canvasses and made papier-mâché masks. He met Mom at a party where she was the only one in costume, a Groucho Marx mask perched atop her petite nose, thick black framed glasses not quite hiding her hazel eyes. They bought a dilapidated building on the Lower East Side with other artist bohemians, clearing out hypodermic needles and long forgotten stuffed animals molding in airshafts. My parents raised my younger brother and I in this rough neighborhood, also surrounded by bits of beauty, Chico’s murals spray painted in pastels on crumbling brick walls, sneakers dangling dancing silhouettes from streetlamps in the summer dusk. And despite major artistic successes, like his permanent mosaic murals in the 2/3 Christopher Street subway station and painted panels mounted in the lobby of the University Settlement, Dad’s social work career and nurturing his children sometimes overshadowed the wild artist’s life he had led. Now, with my brother living in L.A. and me on my own, I sat down with Dad in my parent’s living room filled with naïve art and antique furniture rescued from dumpsters to talk with my father about his Midwest roots, how movies inspired his fantasy life, his own parents and the custom made suit he wore only once.

ROYAL YOUNG: The first thing I wanted to talk about is your move to New York from the Midwest. Why did that happen?

LEE BROZGOL: When I was in Seventh Grade I had a teacher, Francis L. Swift and she was one of my mentors, a really wonderful woman. At that time, she was not very well liked by many of the students and they used to call her “bag bust, because I don’t know if she wore a bra or not, but she had very low hanging breasts. She lived with another woman and there were rumors. But she was very spirited and she had great faith in me. That’s when I started to blossom intellectually. After I had been in New York, I was still living on East Ninth Street in my first year, she called me and I said “How did you know I would be here?” and she said “There are certain people you know will be in New York.”

In my last year at the University of Chicago, I was sitting in my dorm room and it was a very gloomy late winter day. I was sitting on the radiator, looking out the window at the big, grey sky, thinking about what I wanted to do with my life. In my wildest dreams I would be a film director. That was it. It was very inspiring. After that the decision was, do I want to go to Hollywood and make glossy movies, or go to New York and make independent film.

YOUNG: When you talk about wildest dreams, do you think it’s important to raise the bar that high with your ambitions?

BROZGOL: That’s what I did. I don’t think that’s what everybody has to do. When I was that age, early twenties, I was planning my life and I had to decide what kind of life I wanted to live. Why would I want to be a clerk? That’s not what I wanted to be. Sky was the limit.

YOUNG: Why or how did you feel that way? I think a lot of people don’t have the self-esteem to say “I can do whatever I put my mind to.”

BROZGOL: I don’t think there was self-esteem involved.

YOUNG: What was involved?

BROZGOL: When I was a kid, every Saturday, I would go to the movies. It was very important because my home life was extraordinarily drab and ordinary in a very unhappy way. Having the excitement of going to see a film every week was a way of bearing what was so mundane.

YOUNG: Did you go alone?

BROZGOL: Yes, very often I went alone. I took two buses. The second bus took me to the end of the line, where the theatres were, near the lake. The Uptown Theatre was one of the last movie palaces, there were two, one on either side of the street. The Uptown was extraordinarily lavish and across the street was the Riviera. The Uptown always showed the prestigious first tier films. The wall of the Riviera was used as a billboard. So, it was not only going to see what was at the Uptown, which was always the classy A movie, but what was coming to the Riviera next week. The movies for me were an antidote. Making them would have been entering into that world and helping to create the illusion.

YOUNG: Are you saying that this glamorous escape world the movies become for you, later enabled you to take what you wanted?

BROZGOL: I think the bottom line is I loved the movies. They represented a life I didn’t have and wanted. What better way than to make the thing that took you out of your misery?

YOUNG: How did that work out once you got to New York?

BROZGOL: [laughs] Not well at all. It was terrible. Because it was real life, schlepping fucking cans of film around, the film business sucked, it was an industry, it was commercial, it was not about art at all.

YOUNG: After this disenchantment with the film business in New York, how did that translate into visual art?

BROZGOL: I decided if I was going to be an artist, I needed to be an artist completely on my own terms. If I was going to make movies, I would make my own movies. I got into Cooper Union and began to do paintings, drawings, learning the craft of being an artist. My parents were very discouraging of it.

YOUNG: Why?

BROZGOL: They thought I wouldn’t make any money. Even when I went to Cooper Union, when I chose to study fine art, they were like “How could you do that? At least as a commercial artist you’ll make some money.”

YOUNG: Do you feel like moving to New York and being away from your parents allowed you to open up as an artist?

BROZGOL: Yes. It gave me the opportunity to begin to define myself. I never really cared about money that much. I figured if I could eat, pay the rent and get by, I’ll manage. Not caring money allowed me to explore in a way that I couldn’t have if I’d wanted a conventional life. Once I had a suit custom made, a really nice suit that looked well on me. On my way to the subway station, I found in the garbage a Wall Street Journal and tucked it under my arm. There I was in the subway in a really nice suit with a Wall Street Journal under my arm. Not who I am. This gentleman came up to me, clearly a Wall Street type and struck up a conversation. It blew me away, because I could have lived another life. There is another life. But it was not a life that ever appealed to me. Even when I was in high school, I was the Beatnik. That always drew me. There was a whole set of values implied in that, which was very antithetical to what my parents wanted for me. When I was a kid, I was drawing, I wanted to be an artist. It was just a matter of time. That was an aspect of my identity that was hardwired. Like the grass under the sidewalk, it had to grow and would push away the sidewalk. I was never trying to be an artist, or a beatnik, or fringe. It just came naturally. They couldn’t beat it out of me.

Comments are closed